As early as 1654 a congregation of religious dissenters were meeting in secret on a farm at Cilgwyn, between the Teifi and Aeron valleys, near Llangybi. Dissenters faced opposition from the Anglican establishment, but among their early leaders in Ceredigion was a vicar, ejected from his parish in Llanbadarn Fawr for refusing to renounce his dissenting views.

In the 1670s dissenters were given some freedom to worship, including the right for licensed preachers to hold meetings. By 1715 the Cilgwyn group of meeting houses had over a thousand members, or 'listeners' and the area became an early stronghold of Presbyterian nonconformism.

Unitarianism and the 'Black Spot'

Jenkin Jones was ordained as a minister in the Cilgwyn group in 1726. He began to preach the doctrine of Arminianism. (a belief that man had freedom of choice and could achieve salvation through his own deeds, rather than accept that everything was preordained by God).

In 1733, Jenkin Jones built a chapel at Llwynrhydowen, in Ceredigion - the first Arminian chapel in Wales. Several other congregations in the area also adopted Unitarianism. Today, in an area between Llandysul, Lampeter and Aberaeron there is a cluster of 13 Unitarian chapels. The area was dubbed by disapproving 19th century Presbyterians, frustrated by the strength of the Unitarian churches in the area, as the 'Black Spot'.

Llangeitho - revival and the growth of Methodism

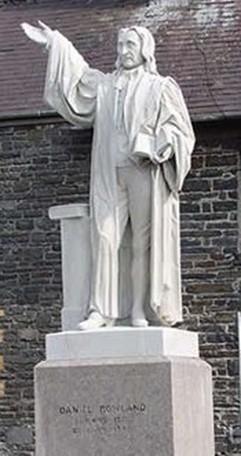

Meanwhile, at Llangeitho, in the upper Aeron Valley, a Methodist revival was taking place. At the heart of the movement was the charismatic preacher, Daniel Rowland, who was attracting crowds from far and wide. Daniel Rowland had been ordained a priest in the Anglican church in 1735. The same year he underwent a spiritual conversion on hearing Griffith Jones of Llanddowror preach at Llanddewi Brefi, and his whole style changed.

Rowland's impassioned preaching sent the crowds that gathered to hear him into rapture, chanting ‘Gogoniant’ (Glory [to God] ). Daniel Rowland, along with his contemporary and friend, Howell Harris, laid the foundations of Calvinist Methodist movement in Wales.

Daniel Rowlands became known as 'the angry cleric' and was hailed by his contemporary, the hymn-writer William Williams Pantycelyn as 'Boanerges, the son of thunder’.

The passion continued into the 20th century, with Dr Martin Lloyd Jones, a medical doctor and charismatic evangelical preacher raised in Llangeitho, who became the minister of Westminster chapel. He is commemorated in the village with a plaque on his childhood home (now the village shop and cafe).

A mission to the world

After becoming an informal meeting place for non-conformists in the Aeron Valley, Neuaddlwyd was formally licensed for worship in 1746. In 1810 an academy was established under the guidance of Thomas Phillips, for training young men from poorer backgrounds who could not afford a university education. Over the next 30 years, over 200 were trained for the ministry in a range of denominational churches across Wales and beyond. Its fame spread as far as America as Thomas Phillips received an Honorary doctorate from what is now Princetown University.

Two of the best known of the students trained by Thomas Phillips were boys from local farms: David Jones and Thomas Bevan, who as young men both recently married, went to Madagascar for the London Missionary Society as the country's first Christian missionaries in 1818.

Enclosure, tolls and lock-out

A sympathetic landlord was important for the well being of his tenants. Enclosure acts fo the 18th and 19th centuries, and the failed harvest of 1816 led to people emigrating to seek a better life in emerging nations such as the United States, Canada and Australia.

In 1819, Augustus Brackenbury from Lincolnshire used half his inheritance to purchase common land from the Crown. Local people, fearing that they would lose their grazing and peat cutting rights, rebelled against Brackenbury, attacking the house he built. He then built a moated house with guards, which was also burnt, although remains can still be seen. He built a third house, optimistically calling it 'Cofadail Heddwch' (Peace Monument) after which he was left alone. Read about the conflict in Eirian Jones’ book, ‘The War of the Little Englishman: Enclosure Riots on a Lonely Welsh Hillside’ (Lolfa).

A decade after the protest of cottagers and craftsmen against Brackenbury, the Rebecca Riots affected Ceredigion and west Wales, as men dressed as women ('Rebecca' and her 'Daughters') brought their own form of rough justice to the town and countryside. This was ostensibly a protest against the tollgates on the turnpike roads which made the use of roads expensive. The riots were also about the general economic conditions and the relationship between farmers and landlords and the demand for cash tithes for the church, resented in non-conformist west Wales.

A later champion of the people against landlordism and strong supporter of tenant farmers in the tithe war, was Unitarian preacher, William Thomas, better known by his bardic name, Gwilym Marles. His reforming zeal and impassioned preaching antagonised the local landlord. resulting in confrontation in 1876 when he and his congregation were evicted from the chapel of Llwynrhydowen, which became known as 'Y Troad Allan' ('the turning out' or 'lock-out'). Undeterred, the congregation opened a new chapel nearby, known as the Memorial Chapel. When the unforgiving young landlord died, his sister gifted the 'old' chapel back to the congregation, but Gwilym Marles' health was broken by the strain and he died prematurely, aged 45, a few months after the new chapel opened. His great nephew was Dylan Thomas, whose middle name, Marlais, reflects his great uncle’s chosen bardic name, Marles.

Smuggling - an unsavoury trade

For most of the 18th century, smuggling was a popular and lucrative activity for many along the Ceredigion coast. During The Napoleonic Wars, there was a heavy duty on imported goods. The tax on tea, for example, was as much as 70% of the cost of the tea itself.

Other goods that were heavily taxed were wine, salt, spirits and tobacco. The tax on salt was particularly unpopular as it was used for pickling, and for salting fish. The tax on salt was lower in Ireland than in mainland Britain, so there was a busy illegal trade.

A mysterious man called John White came to live on the first high bank between the coast at Cwmtydu and the Teifi Valley, known today as Banc Sion Cwilt. John White was a smuggler.

Sion is a Welsh version of John. Some say Sion’s nickname – Cwilt – came from the fact that he wore colourful coats or cloaks made from multi coloured patches. But it’s also possible that it is a corruption of the word ‘gwyllt’ (wild), which would befit a man who rode to meet the smugglers ships.

Sion Cwilt’s ‘one night’ house on the bank was half way between the coast at Cwmtydu and Lampeter, a town on the crossroad of seven roads leading in different directions. Another infamous Ceredigion smuggler was William Owen, a daring and vicious cut throat, who, by his own admission, had killed at least six men before he was captured and hanged in 1747, aged only 30. Unlike William Owen, Sion Cwilt seemed to evaded capture - maybe because he supplied contraband wine and brandy to the High Sheriff of the county who lived at Fynnonbedr, Lampeter.

It is claimed that there is a network of caves near Church Street in New Quay that were excavated specially for hiding smuggled goods. As recently as 2016 a ‘secret tunnel’ was revealed at the back of one of New Quay’s shops.